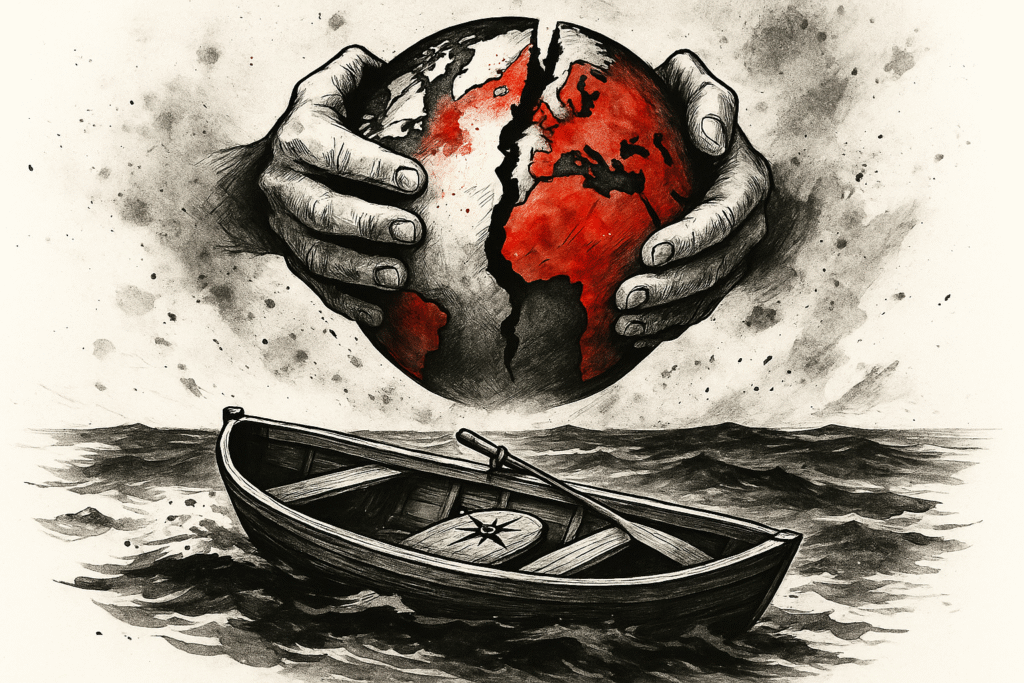

The old order is dying, and the great powers are tearing the world apart like a loaf of bread in pursuit of the coin of hegemony. Yet essentially, the world is in the same boat – and that boat is lost somewhere deep in the ocean of geopolitical uncertainty, without an oar, compass, or helmsman.

Although multipolarity sounds like a great opportunity for small states to find their voice on the global stage, historically, this has been a time when great powers hear few, focusing solely on their own geopolitical interests.

World orders arise from global imbalances of power and influence, whether in the form of a single, dual, or multiple power poles. Studies in international relations show that the most stable order was bipolar, which is why the Cold War, despite the danger of nuclear annihilation, remained cold. Another feature of bipolarity is that it left room for neutrality – which allowed Yugoslavia to remain outside both opposing blocs and secure a measure of economic prosperity.

However, due to its reluctance to abandon communism and open its doors to neoliberalism, the collapse of Yugoslavia followed the end of the bipolar order. On the other hand, U.S. hegemony also proved to be unsustainable and unstable, leading to its weakening in many areas. Francis Fukuyama merely captured the spirit of the time when he declared we had reached the “end of history” at the moment the U.S. stood as the sole great power on the international stage. Today it is clear that the violent spread of liberal values through “crusades” is not a sustainable solution.

The myth of a just order

On the flip side of the same coin are the advocates of a multipolar world, who believe this kind of global arrangement will be fairer to smaller states. Perhaps so – but only if international organizations survive their current existential crises and if great powers abandon their long-term realpolitik goals. Today, the world reflects Machiavellianism more than humanism, so it is easy to conclude that multipolarity is not heralded by heavenly trumpets, but by the four horsemen of the apocalypse.

The world has already been multipolar in two historical periods – both followed by world wars. After World War I, the warring parties established the League of Nations, intending to prevent similar crises in the future through multilateral dialogue. The institution collapsed, and the world plunged again into a global conflict – worse than the first.

From the ashes arose a new institution – the United Nations – with the same mission, but greater commitment. However, the historical events of the past 80 years have shown the UN’s inability to resolve international challenges without the support of great powers.

As U.S. geopolitical power wanes, the world is moving toward multipolarity. But the global chessboard is no longer one-dimensional – the great powers are now playing on multiple boards at once, be it military, political, or economic.

Militarily, we still live in a unipolar world in which the U.S. remains the only power capable of projecting military force anywhere. Economically, the world has long stepped into multipolarity – from Beijing to Brussels to Riyadh, centers of power are multiplying.

Politically, however, the global order is in a state of deep confusion – lost between systems. What will emerge from this process remains unclear, but it is evident that great powers are pushing the world toward political multipolarity – and thus toward new conflicts.

A political vacuum

Although it holds the status of a great power, Russia is militarily trapped in Ukraine, preventing it from projecting power beyond Eastern Europe and Central Asia. In practice, Russia is a global power with regional capabilities. This is, however, good news for the Kremlin – it means Russia does not pose an existential threat to the U.S., something the current American establishment has come to understand.

The primary focus of the United States has shifted to containing China, the only country that can seriously challenge American global dominance. Trump wants to extinguish fires in Europe and the Middle East as quickly as possible to fully refocus on the Southeast Asian region. As a result, the White House has shown little willingness to engage in a larger conflict with Iran, insisting instead on a diplomatic solution. Military aid to Ukraine has been reduced, while European NATO members have come under pressure to increase their defense budgets to five percent of national GDP.

With a higher military budget, Trump can argue that Europe is capable of defending itself, giving him the perfect excuse to relocate U.S. troops from Europe and deploy them across Southeast Asia. The White House’s attitude is clear: “Europe, take care of yourself.”

The gradual American withdrawal from the Balkans has already created a political vacuum that various centers of power are trying to fill. Politically, the most active actors are France and Germany, while Russia and China, apart from economic and cultural influence, lack the capacity for broader power projection.

Although the White House insists on strengthening NATO’s European members, no great power is truly interested in a unified Europe with enhanced military and political strength. Southeastern European countries could play a more important role in the new U.S. foreign policy strategy, where by empowering those states, Washington would aim to contain the military and political rise of the European Union.

The “Three Seas Initiative,” which brings together 17 countries from Eastern and Southeastern Europe, could also gain importance. The new U.S. administration has shown certain sympathies for the Serb issue. Thus, the choice of Mark Brnovich as the new U.S. ambassador to Serbia should not come as a surprise, signaling that the Balkans are high on the list of geopolitically important regions for Trump’s administration.

On the other hand, due to its strategic importance, we may see certain concessions and a greater political comeback by Turkey in the Balkans. Turkey has shown readiness to increase its military presence in international missions in Kosovo and Metohija and in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Small states can survive geopolitical conflicts only through realpolitik. For the Serb people, this would imply a kind of ideological exorcism – both from communism and from the naïve belief in salvation through great powers. In a world defined by Machiavellian principles, sovereignty is achieved through the acceptance of limiting realities – and the courage to forge an autonomous path.

Source: Glas Srpske