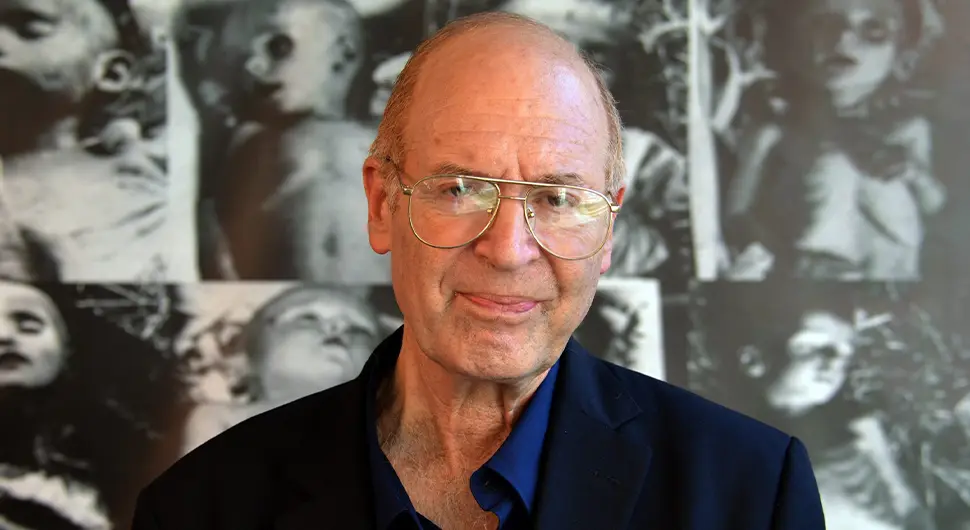

Gideon Greif, Chairman of the Independent International Commission for the Investigation of Suffering of All Peoples in the Area of Srebrenica from 1992 to 1995, explained in an article for “Weltwoche” why there was no genocide in Srebrenica.

The article published in “Weltwoche” is presented in its entirety:

The report of our commission was agreed upon, accepted, and signed by all members of the commission. This means that the report has collective authorship of all members of the Commission, and not of an individual, even if he is the chairman. I am proud to have had the opportunity to work with such a group of exceptional people and world-class experts.

During our two-year research work, we discovered that two major massacres occurred in the area of Srebrenica during the civil war in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1992 and 1995. The first occurred from April 1992 to April 1993 against the Serb population, and the second from July 14 to 16 on the largest group of captured Bosnian soldiers of the active and reserve troops of the 28th Division of the Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Although the term “genocide” is widely known, it did not exist before the rise of the Nazi regime to power. In 1941, Winston Churchill described the crimes committed by the Nazis during the invasion of Russia as “a crime without a name”. It was not until 1944 that Polish-Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin (1900–1959) introduced the term “genocide” in his book “Axis Rule in Occupied Europe”, where he described the destruction of national and ethnic groups, including the mass-documented murder of European Jews. He combined the Greek word for race or tribe, “geno”, with the Latin word for killing, “cide”.

In its resolution 96 (1) of December 11, 1946, the United Nations General Assembly declared that “genocide” is a crime under international law, contrary to the spirit and aims of the United Nations and condemned by the civilized world.

Two years later, the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was unanimously ratified by the United Nations General Assembly and adopted as Resolution 260 on December 9, 1948. The convention entered into force on January 12, 1951. All participant states are recommended to prevent and punish genocide in both war and peace.

Article 2 of the Convention defines genocide as follows: “For the purpose of this convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group, as such: (a) killing members of the group; (b) causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; (c) deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; (d) imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; (e) forcibly transferring children of the group to another group”.

According to this article, genocide consists of two constitutive elements: the physical element, that is, the act committed, and the psychological element. These two elements are connected, even if they are analytically distinct. “Intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group, as such” is the essential characteristic of genocide, which distinguishes it from other serious crimes.

According to Article 4 of the Statute of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), genocide consists of the intentional destruction of “a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group”.

This has been one of the most controversial aspects of the definition of genocide. Critics have complained about the limited scope of the definition and the exclusion of political and other groups and have proposed amendments to broaden the scope. Alternatively, they argued that judges should adopt a dynamic interpretation of the provision. However, when states had the opportunity to revise the definition at the Rome Conference in June and July 1998, they decided to reaffirm the text adopted by the United Nations General Assembly fifty years earlier.

Looking at the numbers, it seems questionable that a significant part of the Muslim population of Bosnia was wiped out by killing several thousand men. According to the ICTY Demographic Unit, it is estimated that 69.8 percent, or 25,609, of the civilians killed in the war in Bosnia were Muslims (out of 42,501 military deaths), while the Serbs had 7,480 civilian deaths (15,299 military deaths), and Croats had 1,675 civilian deaths (7,183 military deaths), totaling 104,732 deaths distributed among Croats (8.5 percent), Serbs (21.7 percent), Muslims (65 percent), and others (4.8 percent). During the entire war in Bosnia, 1.32 percent of Muslims were killed. In Srebrenica, less than 0.4 percent of the Muslim population was killed. The proportion of Muslims in the total population of Bosnia and Herzegovina actually increased during the war. On both the Serb and Muslim sides, there were about twice as many military casualties as civilians; on the Croatian side, the ratio was even higher. This clearly argues against a form of genocide that would require a much higher overall mortality rate and many more civilian casualties.

The classical genocides of the 20th century – the genocides of European Jews and Rwandan Tutsis – are significant for their insistence on killing women and children to ensure that the group is truly exterminated. The question, however, is not whether the massacre of military-capable men and boys really destroyed the Muslims in Srebrenica. The crime of genocide does not require an outcome, and courts are not obliged to determine whether the actual method was well-chosen. However, if the technique of genocide is incomplete and perhaps illogical, it will raise doubts about whether there was indeed an intent or not. The crimes committed in Srebrenica in July 1995 can certainly be described as “crimes against humanity”. However, calling it “genocide” seems to unjustifiably distort the definition.

After assessing the facts of the massacre, no specific intent to exterminate the population of Srebrenica as such can be established. There is no apparent intent to destroy the entire Muslim population. Killing several thousand prisoners of war and a few hundred military-capable men from the Srebrenica region would not provide any general advantage to the Serb leadership, as it assumed that the area of the enclave would be annexed to Republika Srpska as part of the ongoing peace negotiations. This would have prevented the Muslim population from returning to Srebrenica anyway, even if the military-capable men from the enclave had remained unharmed. The large number of members of the column composed of active and reserve units of the 28th Division of the Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina also suggests that many fighters came from areas outside Srebrenica, so the column does not represent a group of military-capable men from Srebrenica. It is also clear that by July 12, 1995, there was no order to kill all captured Muslims. The Tribunal’s chambers were convinced that such an order had to be given the next day.

Genocide as such could not have happened in Bosnia. Since the crime of genocide, by its nature, presupposes the intent to destroy at least a significant part of a specific group, genocide as such can only occur when a significant part of a specific group is physically destroyed. This destruction must be established as an objective fact. As previously mentioned, “a significant part” does not have to be measured by the total number of victims, although this is always the first applied test. The ad hoc extermination of less than 0.4 percent of the Muslim population of Bosnia and Herzegovina within a few days does not mean that genocide against the entire group occurred.

Finally, a few words about what I consider one of the main achievements and impacts of the Commission’s work and the publication of our report. As far as we, the members of the Commission, could later determine, after the publication of our report, no one in Republika Srpska or Serbia denied the crime committed in July 1995. Unfortunately, we note that on the other side, no one, officially or unofficially, was willing to acknowledge the mass and systematic crimes committed by the Muslim army against the Serb population. In this context, it is crucial to emphasize that one of the fundamental values of civilization is the freedom of academic and professional research of historical events and the freedom of mind, no matter how controversial and painful they may be. It is important to understand that propaganda always tries to prevent academic re-examination of its media policy narratives in every possible way.