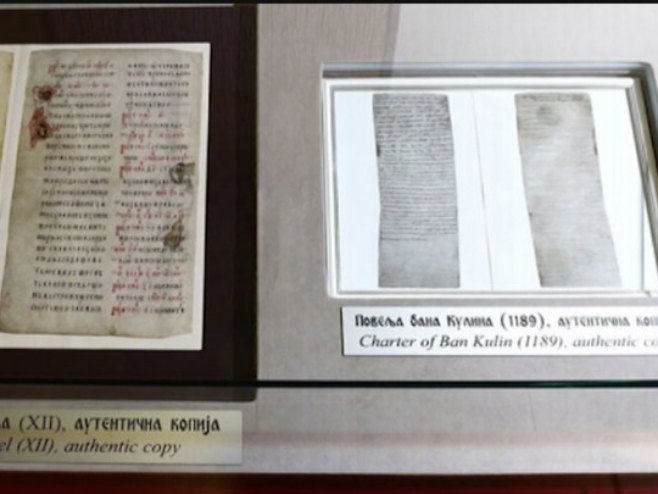

While falsifying and attempting to appropriate the cultural and historical heritage of the Serb people, including the Charter of Kulin Ban, Sarajevo historians and philologists even mark its anniversary on the wrong date. The Charter of Kulin Ban was written on the Beheading of St. John the Baptist – September 11, 1189, according to the new calendar, or August 29 by the old calendar. Scientific facts are undeniable: the Kulin Ban Charter reflects all the linguistic changes that had entered from the vernacular into Church Slavonic by the 12th century. Ban Kulin was a Serb nobleman of Orthodox faith who ruled only part of what is today Bosnia.

The distorted and Bosniak-influenced version of medieval Bosnian history is centuries apart from the actual past, and it has been nine centuries since Kulin Ban and his “good days.” In the absence of evidence for Bosniak historical rights or monopoly over Bosnia, quasi-academic circles resort to appropriation, claiming that Bosnia is not the product of modern times and international arrangements, but has supposedly existed as a state for centuries.

The renowned Croatian Slavist Vatroslav Jagić, had he found any doubt about the Serbian character of the Charter, would not have written in his Memoirs: “The charter of Kulin Ban from the year 1189 is the first and oldest written in Cyrillic and in the Serbian language.” The text of Kulin’s charter clearly sounds Serbian:

“In the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit. I, Bosnian Ban Kulin, promise you, Prince Krvaš and all citizens of Dubrovnik, that I will be a true friend to you from now and forever. I will uphold justice with you and true trust as long as I live.”

Only Serbian Cyrillic recognizes the letter “Ћ.” Apart from Kulin’s Charter, it also appears on his donor’s plaque as well as in numerous other documents of that period.

“It is interesting that this letter also appears in the Miroslav Gospel—Miroslav being Kulin Ban’s brother-in-law, married to his sister. In Kulin Ban’s Charter, as well as in the Hilandar Charter of Grand Župan Stefan Nemanja, one can see the cultural unity and a shared language. The Charter can also be compared with donor inscriptions from Studenica, the first monastery where Cyrillic was used,” explains historian Dejan Došlić.

In essence, Kulin’s Charter—essentially a simple customs document by today’s standards—granted Dubrovnik merchants the right to travel freely where he ruled, to trade wherever they wished, and bound himself to offer them protection with the words: “So help me God and this holy gospel.”

“It is important to point out that, from its invocation of the Holy Trinity to its signatures and mention of witnesses, this Charter resembles those of the Nemanjić dynasty and other medieval noble families of the same rank, name, and origin. Bosniak historiography abuses Kulin Ban’s Charter to construct a supposed tradition of Bosnian statehood. This is impossible—an artificial interpretation without any basis in historical truth. Such claims do not honor either historians or legal scholars who attempt them,” emphasizes legal expert Marko Romić.

Equally absurd is the claim that the Charter was written in a so-called Bosnian language or Bosančica. By 1187, even Pope Clement III referred to Bosnia as part of the “state of Serbia” when he granted church rights to the Archbishop of Dubrovnik—clear proof that medieval Bosnia was part of the Serbian state.

Source: RTRS