At a session held on November 2nd this year, the United Nations Security Council discussed the situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and notably, the self-proclaimed and false High Representative, Christian Schmidt, was not in attendance.

When the General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina was initialed in Dayton on November 21st, 1995, and subsequently signed in Paris on December 14th, 1995, it was not anticipated that the “Dayton Bosnia and Herzegovina“ would to this day be marked by the presence of the High Representative, foreign judges within the Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and unauthorized interference by Sarajevo’s ambassadors – the Quint, or more accurately sepsis – in the internal matters of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

High Representative Not Mentioned in the Dayton Agreement

The High Representative is not specified in the General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina, commonly known as the Dayton Agreement. In the text of the Dayton Agreement, there is no mention of the High Representative at all, and its Article 8 only acknowledges that the “Parties welcome and endorse the arrangements that have been made concerning the implementation of this peace settlement, including in particular those pertaining to the civilian (non-military) implementation, as set forth in the Agreement at Annex 10.” Hence, the role of the High Representative is not formally established within the Dayton Agreement itself, but rather within its Annex 10, titled “Agreement on Civilian Implementation of the Peace Settlement,“ signed by The Republic of Srpska, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the “Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina“ (which did not exist back then, and much less now), Serbia, and Croatia. If the intention was for the High Representative to serve as an officer of the entire civilian part of the Dayton Agreement, the text would have included specific mention of the High Representative within the Dayton Agreement itself. However, this is not the case.

The High Representative’s authority is limited to interpreting only Annex 10, and not any other section of the Dayton Agreement. This “confines” and establishes the High Representative’s scope exclusively within Annex 10, defining the responsibilities and tasks of the High Representative as set by the signing parties. It is crucial to note that there is no mention of the High Representative in the most significant annex of the Dayton Agreement – Annex 4, that is, the Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

High Representative Has Neither Executive nor Legislative Powers

The mandate of the High Representative does not contain any provision granting the authority to issue decisions binding upon the authorities and citizens of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Despite frequent assertions, both spoken and written, that the High Representative is the ultimate or supreme interpreter of the Dayton Agreement, no specific article from the Dayton Agreement or its annexes is cited to confirm this, except for the misleading mention of Article 5 of Annex 10 titled “Final Authority to Interpret.” This article explicitly states, “The High Representative is the final authority in theater regarding interpretation of this Agreement on the civilian implementation of the peace settlement.”

Every legal interpretation, whether in terms of language or logic, affirms that the authority for interpretation is restricted solely to one specific annex of the Dayton Agreement – Annex 10. However, the right to interpret only that annex does not confer any executive or legislative powers to the High Representative. Contrary to this, High Representatives have, for many years, unlawfully assumed the roles of legislative, executive, and judicial authorities. They forcefully introduced amendments to the constitutions of both the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and The Republic of Srpska, as the parties involved in appointing the High Representative. Additionally, they forcefully imposed laws transferring the competencies of entities to the national level of Bosnia and Herzegovina. They claimed legislative authority for themselves, despite such privileges not being referenced even within the so-called “Bonn Powers.” High Representatives replaced elected officials, confiscated their personal documents, and prohibited their work without providing any explanation or opportunity for appeal, resulting in a significant breach of numerous human rights conventions that are an integral part of the Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

PIC Could Not and Did Not Grant Authority to the High Representative

The Peace Implementation Council (PIC), labeled as an “informal group of states” by the European Court of Human Rights, is a remnant from the Peace Conference on Yugoslavia from the early 1990s, a period marked by the crisis of disintegration and the collapse of the SFR Yugoslavia. This residual assembly, named the PIC, continued with their meetings even after the end of the civil war in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Carl Bildt wrote that on December 8, 1995, in London, a meeting of foreign affairs and defense ministers had taken place, leading to the formation of the PIC. During this gathering, “a core group of eight nations was established as the Steering Board, and the High Representative was appointed as its chair. After considerable deliberation, I took on this role for a year.” This implies that there was an initial plan for a one-year mandate for the High Representative.

The Peace Implementation Council was not formally established by any international authority, and there was no designated procedure for selecting its members or defining its composition. There was no founding document or any official operating guideline. Some authors labeled the PIC as a “self-appointed entity of self-appointed countries.” Several conferences were held, with the most recent occurring in 2000, suggesting the self-appointed entity essentially disbanded. Its residual component, the Steering Board (a body that continues to function without a clear basis in the PIC’s official documents), meets twice a year in Sarajevo, primarily at the ambassadorial level, occasionally with the participation of political directors from member countries’ foreign ministries. The process by which this Steering Board was assembled remains unclear. In addition to the countries that witnessed the signing of the Dayton Agreement in Paris in 1995 (USA, France, Germany, UK, Russia, European Union), other members of the Steering Board include Italy, Japan, Canada, and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, represented by Turkey. Notably, the Steering Board does not include Serbia (formerly FR Yugoslavia) and Croatia, both signatories to the Dayton Agreement. Furthermore, as stated in the preamble of the Dayton Agreement, Serbia (FRY) signed the agreement on behalf of The Republic of Srpska, with the authorization granted by The Republic of Srpska. It appears that membership in the Steering Board is deemed more important for Turkey, representing Islamic countries, or far-away Japan and Canada, compared to the two signatories of the Dayton Agreement – Serbia and Croatia. The rationale behind the absence of Vatican membership as a Catholic state, as well as the lack of representation from any of the Orthodox associations, given the criteria used for the participation of Islamic countries, remains unclear.

The configuration of the PIC lacks any legal foundation to grant it authority or rights under the Dayton Agreement and its eleven annexes. Consequently, the PIC was never able to appoint High Representatives or endow them with any form of jurisdiction. Moreover, even the Peace Implementation Council did not confer any powers upon the High Representative, despite stating that it “welcomes the High Representative’s intentions.” Even though the phrase “welcomes the High Representative’s intentions” is nothing but an arbitrary choice of words as well as a legal absurdity, it was meant to be presented as an authorization. This led to the creation of the so-called “Bonn Powers.” With the media and subsequently politicians adopting this terminology, the term “Bonn Powers” became an empty phrase that has persisted for 26 years. Consequently, the High Representative has transformed into an entity with boundless authority in Bosnia and Herzegovina and without any accountability for their actions. It is typical for this official, established by foreign signatories of Annex 10, to be referred to as the “High Representative of the international community,” which is one of the deceptions and self-attributed false titles, eventually accepted by others.

As previously mentioned, the PIC lacked the authority to grant any powers to the High Representative, and, thus, it did not grant them any. During the Bonn Conference held in December 1997, the PIC, in Chapter 11 of its conclusions, “welcome[d] the High Representative’s intention to use his final authority in theatre regarding interpretation of Annex 10 to the Agreement on the Civilian Implementation of the Peace Settlement in order to facilitate the resolution of difficulties by making binding decisions, as he judges necessary,” specifically, “on the following issues: a) timing, location and chairmanship of meetings of the common institutions; b) interim measures to take effect when parties are unable to reach agreement, which will remain in force until the Presidency or Council of Ministers has adopted a decision consistent with the Peace Agreement on the issue concerned; c) other measures to ensure implementation of the Peace Agreement throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina and its Entities, as well as the smooth running of the common institutions. Such measures may include actions against persons holding public office or officials who are absent from meetings without good cause or who are found by the High Representative to be in violation of legal commitments made under the Peace Agreement or the terms for its implementation.”

In interpreting these narrowly prescribed “authorities” more broadly, even when discussing the issues the High Representative himself identified as his powers, despite mentioning the Bosnia and Herzegovina Presidency and the Council of Ministers, the PIC failed to mention the Parliamentary Assembly as a legislative body. Hence, the PIC could not even “welcome the intention” of imposing laws. On the contrary, High Representatives have extensively engaged in this – imposing laws lacking constitutional backing and altering the Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Dayton structure to the detriment of the entities, that is, to the detriment of The Republic of Srpska. Consequently, all the laws imposed by the High Representative are unfounded, even in view of the decisions made during the PIC’s Bonn conference.

When it became apparent that the “welcoming of the intention” lacked the involvement of acts passed by the Parliamentary Assembly, the OHR simply appended the Bonn conclusions. On the official website of the High Representative, you can find the following statement: “Among the most important milestones in the peace implementation process was the PIC Conference in Bonn in December 1997. Elaborating on Annex 10 of the Dayton Peace Agreement, the PIC requested the High Representative to remove from office public officials who violate legal commitments and the Dayton Peace Agreement, and to impose laws as he sees fit if Bosnia and Herzegovina’s legislative bodies fail to do so.” The extent to which this statement contradicts the conclusions of the 1997 PIC Conference in Bonn is utterly absurd.

The act of fabricating and inserting this particular wording on the official OHR website can be deemed as a falsification. More importantly, this act essentially concedes that even the “Bonn powers” did not confer any legitimate authority upon the High Representative to enact laws. This means that all the laws imposed by the High Representatives through their decisions are invalid. When imposing laws, they relied on a fabrication that the OHR incorporated into the conclusions of the PIC’s Bonn Conference of December 1997. This sort of addition constitutes a criminal offense committed by the OHR employees.

As a matter of fact, under the terms of Annex 10, only one High Representative was envisaged, who happened to be Carl Bildt. Article 1, Point 2 of Annex 10 explicitly states: “[T]he Parties request the designation of a High Representative, to be appointed consistent with relevant United Nations Security Council resolutions.” It does not mention “High Representatives” in the plural form. Therefore, after Carl Bildt’s mandate had ended, all individuals appointed without the request and consent of the signatory parties of Annex 10, which include The Republic of Srpska and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, are deemed illegitimate, as their appointment was unlawful.

Carl Bildt Was Sole High Representative Appointed under Annex 10

Regarding the establishment of a framework for civilian implementation, the first High Representative, Carl Bildt, who was approved by the signatory parties to Annex 10, elaborates in his book “Peace Journey” that Washington initially opposed to the idea of having someone “monitoring implementation of the agreement.” Initially, it was envisioned to have an implementation coordinator, per Washington’s stance, to “serve as a point of contact for international and voluntary organizations engaged in realizing the peace agreement,” and they immediately added that this “implementation coordinator would not have any authority over any international organizations, voluntary organizations or functions in the host country […] if he has not explicitly obtained such authority.”

It is a fact that, as per the Dayton Agreement, the High Representative never obtained such authority, as the subsequent so-called “Bonn Powers” did not grant it to him. Carl Bildt made a statement to The New York Times in late December 1995 after the peace agreement was signed, saying, “You seem to overestimate the powers of the High Representative. His powers are not to execute or enforce but to monitor and coordinate.”

The appointment of the High Representative was made at the request of the signatory parties of Annex 10. As per the Annex’s provisions (Article 2, Point 1), the consensus of all five parties is a prerequisite for the High Representative’s appointment. In the case of appointing the first High Representative, Carl Bildt, consultations were conducted with the authorities in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The appointment was subsequently confirmed by the United Nations Security Council. No further consultations have taken place, nor have the signatory parties ever demanded the appointment of additional High Representatives. This raises concerns about their legitimacy and the lawfulness of the procedures for their appointments, particularly in relation to the acts they have adopted without proper authority.

Romeo and Juliet

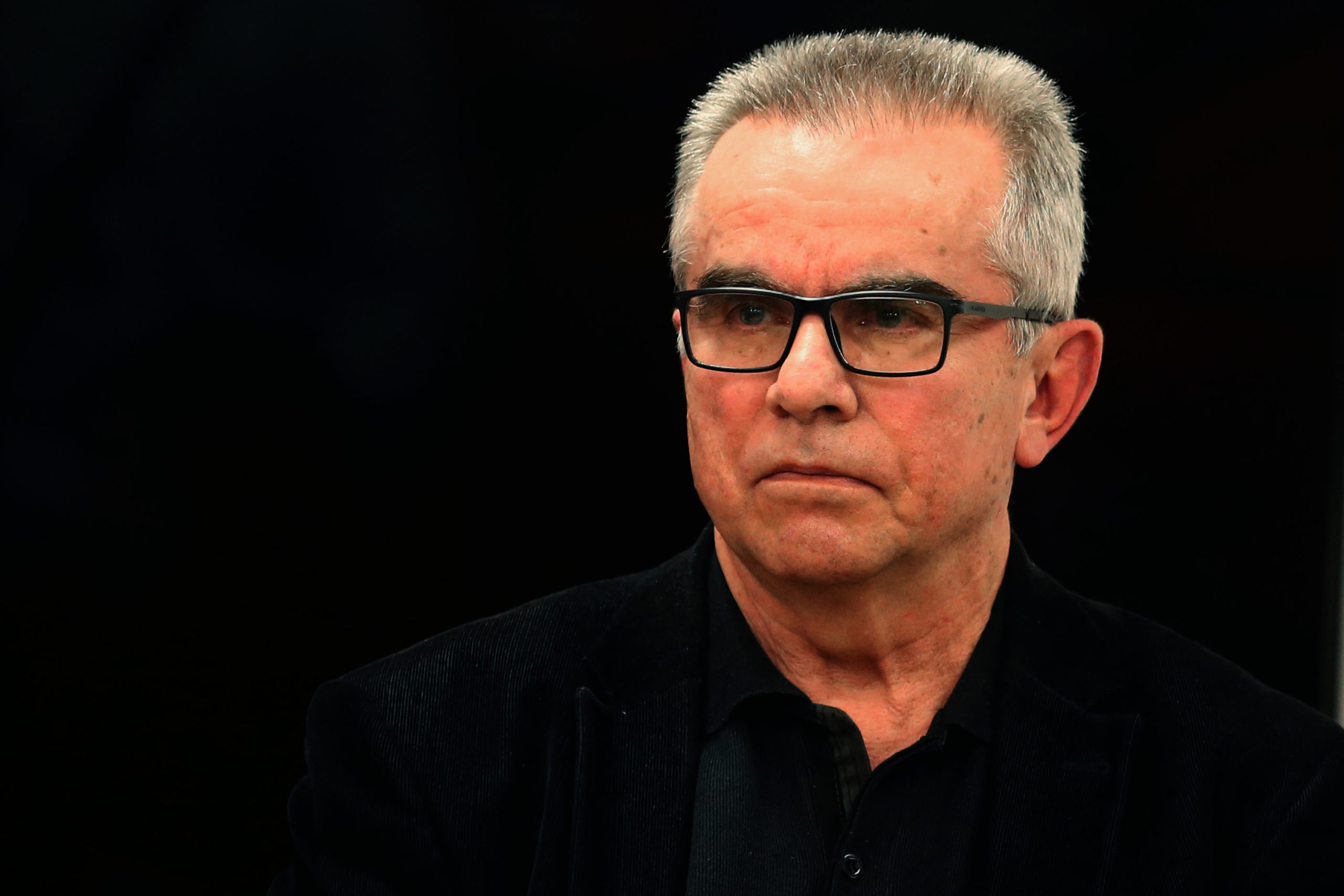

Seven High Representatives later – those whose mandates were at least confirmed by the United Nations Security Council – Christian Schmidt discretely entered Bosnia and Herzegovina. He was apparently “officially” appointed as the High Representative by a cluster of Western ambassadors in Sarajevo, despite lacking the authorization outlined in the Dayton Agreement. There was no request from the signatory parties, as mandated in Annex 10, and The Republic of Srpska made it explicit in the conclusions of its National Assembly, dated March 10th, 2021, that it no longer accepted any High Representative. Moreover, there was no formal confirmation of Christian Schmidt’s appointment by the UN Security Council. Conversely, during the session held on July 22nd, 2021, the UN Security Council refused to appoint Christian Schmidt as the High Representative.

All of this does not stop Schmidt. Thanks to his high monthly salary of a corrupt-official that amounts to about fifty thousand marks, he willingly plays the court jester of several Western embassies in Sarajevo, calling himself the High Representative. It is well known that, after several failed attempts to appoint Schmidt to any position within the country, Germany kicked him right over here for us to deal with him. That criminal-immersed pest is prepared to play any role – Romeo, Juliet (with a wig), an idiot, that hysteric (without the mustache), absolutely anyone. The amount he receives is not small: 25,000 euros, 300,000 annually, totaling 650,000 euros so far. No taxes, and he also receives allowances for travel, accommodations, risks of contaminated water, poor roads, irregular air traffic, and so forth.

Schmidt’s “Laws”

The legal situation can be summarized as follows: The sole legislative authority in Bosnia and Herzegovina lies with the Parliamentary Assembly, consisting of both houses (Article 4.3.c of the Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina). Article 104 of the House of Representatives’ Rules of Procedure at the national level of Bosnia and Herzegovina designates the authorized law proposers, namely, members of parliament, House committees, joint committees, the House of Peoples, the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the Council of Ministers of Bosnia and Herzegovina, all within their respective scopes. The High Representative lacks the authority to propose laws. Therefore, laws imposed by the High Representatives cannot be regarded as submissions for consideration in the Parliamentary Assembly.

The situation that is against the laws can be summarized as follows: Under the “welcoming of the intention” premise, often referred to as the so-called “Bonn Powers,” the High Representative had the authority to enact laws within the jurisdiction of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina or the Council of Ministers up until the moment they made a decision concerning the matter in accordance with the Dayton Agreement. As per the appended conclusions of the Conference held in Bonn, the High Representative was allowed to impose essential laws if the Parliamentary Assembly failed to adopt them. However, safeguarding Schmidt’s personal matters does not qualify as a crucial law, nor was it previously adopted by the Parliamentary Assembly.

Hence, Schmidt was unable to enact laws for three main reasons. FIRST: He himself is not the Parliamentary Assembly. SECOND: The so-called “Bonn Powers” apply to decisions made by the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Council of Ministers, not the Parliamentary Assembly. THIRD: According to the Bonn conclusions amended by the OHR, the focus should be on an “essential law” that was previously refused by the Parliamentary Assembly.

Crimes of Prosecutor’s Office and Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Christian Schmidt – even if he is the High Representative – was never authorized to introduce amendments to the Criminal Code of Bosnia and Herzegovina to protect his own back, as stated by Zoran Milanović, the President of Croatia. Milanović said, “A retired German politician who has not made a mark, in order to protect his own back and reputation, changed the criminal law, according to which what Dodik had done constitutes a criminal act.“ This is called colonial administration, and it destroys a country it is applied in. Bosnia and Herzegovina is a colony. A colony that is clumsily, inadequately, and incompetently led by a handful of third-rate bureaucrats who abuse their authority.

And what do we do now? The Prosecutor’s Office and the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina are conducting criminal proceedings against Milorad Dodik, the President of The Republic of Srpska, who acted in accordance with the Constitution of The Republic of Srpska, and Miloš Lukić, the director of the “Official Gazette of the Republic of Srpska”, who, in accordance with his legal obligation, ordered the publication of laws passed by the National Assembly of the Republic of Srpska. Both men respected the provisions of Article 1.2. of the Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina, according to which “Bosnia and Herzegovina shall be a democratic state, which shall operate under the rule of law and with free and democratic elections.” The President of the Republic of Srpska, Milorad Dodik, was elected through free and democratic elections, and now he is being unlawfully persecuted by Christian Schmidt and the prosecutors and judges of the Prosecutor’s Office and the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina, who are referring to one of Schmidt’s decisions – a decision, which is not a law. And that attempt will fall through. As will Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Author: Slavko Mitrović